When a hotly anticipated finale of television begins with a monologue about accepting a lack of resolution, it’s hard not to start sweating. White Lotus creator Mike White knew exactly what he was doing when he began “Amor Fati” with Luang Por Teera (Suthichai Yoon), the monk Piper (Sarah Catherine Hook) dragged her family to Thailand to visit, giving a speech to that effect.

“Our solutions are temporary—they are a quick fix, they create more anxiety, more suffering. There is no resolution to life’s question,” he says. “It is easier to be patient once we finally accept there is no resolution.”

He might as well have been saying, “Those of you holding out hope for a proper ending to the most divisive season of The White Lotus yet should prepare yourself for disappointment.”

But the trick of the series, at least in its first two seasons, is that it pointedly avoids the expected resolution and ends up delivering a fitting ending all the same. This is a show that’s been built on red herrings, with each season culminating in an anti-climax. We were primed for a murder mystery in Season 1, only to see Armond (Murray Bartlett) stabbed entirely by accident. In Season 2, those gays really are trying to kill Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), but her death is another accident, as she tumbles from a yacht, hits her head, and drowns.

For much of the Season 3 finale, it looks like we’re headed toward a similar conclusion. There are plenty of characters who seem like they could kill or be killed. Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) and her son Zion (Nicholas Duvernay) have decided to demand $5 million from Greg (Jon Gries) in exchange for Belinda’s silence. “Go big or go home, right?” says Zion. “In a goddamn body bag,” Belinda answers forebodingly. Meanwhile, Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong) has figured out that Valentin (Arnas Fedaravicius) and his friends were behind the robbery, and he’s being pressured by Mook (Lalisa Manobal) to take violent action.

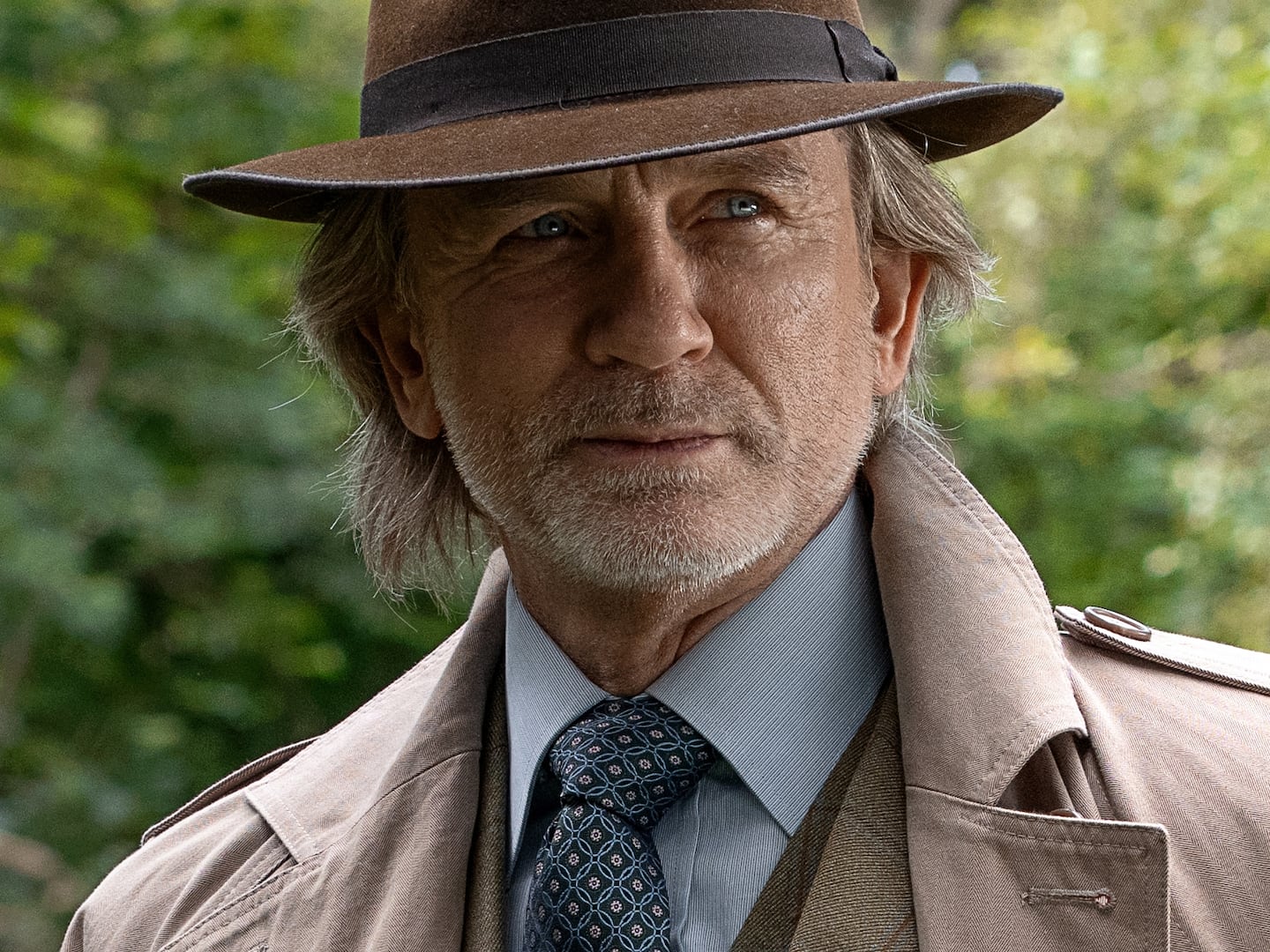

And then there are the Ratliffs, whose patriarch, Tim (Jason Isaacs), is determined to spare his family the indignity of learning about his crimes and losing everything. He prepares a batch of poisoned piña coladas to off everyone except for Lochlan (Sam Nivola), then decides against it at the last minute. When Lochlan makes a protein shake in the tainted blender the next morning, it looks like he’s going to be the season’s accidental casualty—but he ends up surviving. Call it an act of grace in a finale steeped in the divine.

Instead, the big deaths are Rick (Walton Goggins) and Chelsea (Aimee Lou Wood). Rick’s inner peace only makes it partway through the episode before another encounter with Jim Hollinger (Scott Glenn) sends him back on the path of revenge. He shoots and kills Jim just in time to learn that Jim didn’t kill his father—he was his father, a twist just about everyone had guessed. In Rick’s shootout with the White Lotus bodyguards, Chelsea is struck by a bullet and killed. And as Rick carries her body away, he’s shot by Gaitok, after Sritala (Patravadi Mejudohn) demands that the security guard give into his killer instincts.

“Amor fati” is not just the title of the episode—it’s a concept that Chelsea explains to Rick earlier in the finale, a fancy Latin way of saying “whatever will be, will be.” It’s the idea of embracing the uncertainty and throwing up your hands since there’s no way of predicting what fate has in store. As the scene plays out, however, Chelsea’s fate starts to look decidedly grim. “At this point, we’re linked, so if a bad thing happens to you, it happens to me,” she tells Rick. “I think we’re gonna be together forever, don’t you?” At this point, there might as well be a target on her forehead.

Previous finales of The White Lotus have followed the “whatever will be, will be” ethos, underlining the randomness and unpredictability of the universe. There is never a clean ending to neatly tie everything together—no resolution, as Luang Por Teera puts it to his assembled congregation. The Season 3 finale goes in a different direction entirely by following through on the path it’s laid out. You could call Chelsea’s death random in the sense that she’s a true innocent bystander, but it doesn’t feel remotely random if you’ve watched television before.

The entire climax is oddly beholden to TV tropes in a way that this show hasn’t been. It’s not just the age-old story of the reformed criminal giving into his worst instincts and losing the one good thing in his life in the process. The shootout as a whole is a strangely straightforward action-packed conclusion, especially compared to the darkly funny Season 2 shootout, where the violence is almost entirely off-screen.

Then, of course, there’s the dramatic reveal of Jim’s true identity as Rick’s father. It’s not so much that viewers guessed this already, but that it again plays as the most obvious choice for an epic finale—something The White Lotus had eschewed up to this point.

Ultimately, the biggest disappointment of the episode is how much it leans into a kind of pathos that’s typical of less nuanced storytelling than what White usually offers. It’s true that there were other deaths that might have carried the same feeling of inevitability—a Ratliff murder-suicide, or Belinda pushing her luck with Greg and getting herself killed—but going with the death that will hurt the most is its own classic trope. And it turns the show from a pitch-black comedy, a genre where it has thrived for three seasons, into a simpler tragedy.

Perhaps the tragedy itself is the misdirect: A show about people fumbling their way into untimely ends becomes a show about the cruel hand of fate. That’s one way to keep viewers on their toes, but the end result is simply less interesting than the conclusions to the past two seasons.

Thankfully, there are other elements of the finale that are more layered, surprising, and distinctly White Lotus, from Belinda choosing a life-changing amount of money over doing the right thing, to the trio of frenemies (Carrie Coon, Leslie Bibb, and Michelle Monaghan) finding the divine in their sincere love for each other.

It’s really the deaths themselves that ring false, buried in the kinds of tropes that White has previously seemed content to skewer. Even in the nihilism of the show’s closing moments, the finale is the first time The White Lotus has ever felt like it was playing it safe.