It would be easy to crown 2025 the year of Hamlet—quite a feat considering the play was written over 400 years ago.

Over the last 12 months, the tragedy of William Shakespeare’s Danish prince has journeyed across the universes of video game Grand Theft Auto, an anime movie, and a modern-day London-set adaptation. There have been myriad stage productions and a documentary, King Hamlet, about Oscar Isaac’s taking on the titular role in 2017. And let’s not forget Taylor Swift, whose “The Fate of Ophelia” adds another layer to the pop culture smorgasbord.

Now, Hamlet is back home in Stratford-upon-Avon in Chloé Zhao’s historical fiction origin story, Hamnet.

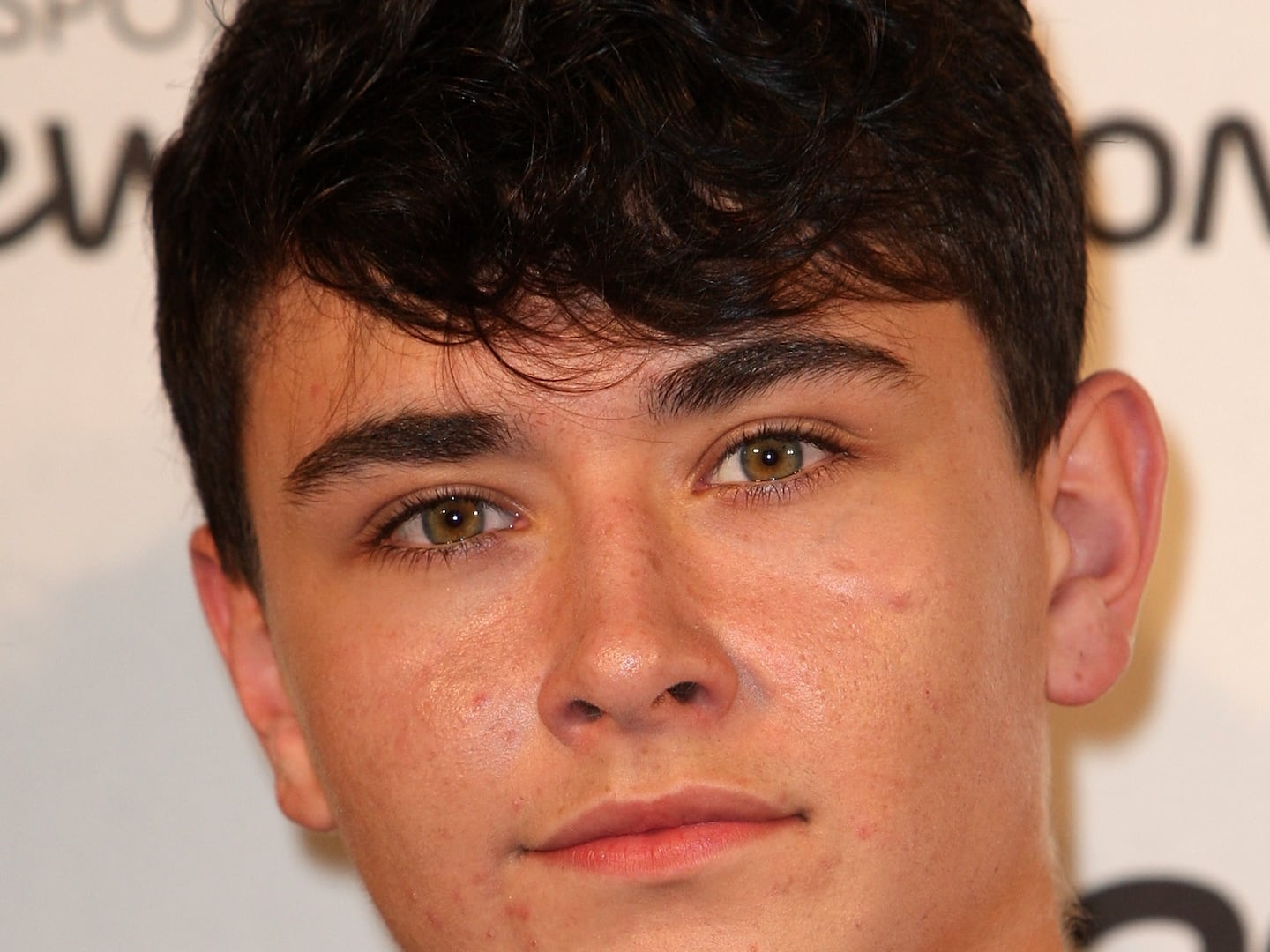

Adapted from Maggie O’Farrell’s novel of the same name, Hamnet takes audiences into the homes of the world’s most renowned playwright. Rather than focusing only on Will (Paul Mescal), it’s his herbalist wife, Agnes (Jessie Buckley), who takes center stage in the film—as does their romance. Their son Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) serves as inspiration for the play’s near-namesake; it is not a spoiler to say things do not end well for the 11-year-old.

Zhao’s emotional meditation on life, death, and art—which is now in limited release and opens wide on Dec. 12—is dominating awards conversation as the year winds down. Given Shakespeare’s centuries-spanning popularity, it is hardly surprising this story is resonating.

The global significance is something I have seen firsthand my entire life; Stratford-upon-Avon is my hometown. While reading the novel and then watching the movie, I couldn’t help but picture the place I grew up in, with its thatched roofs, three permanent theaters, and nods to Bill on every street corner and pub interior—regardless of whether its doors opened in the 16th or 21st century. In Stratford, you can trace Shakespeare’s steps from birth to death; you can even sit in his classroom.

I spoke to Hamnet production designer Fiona Crombie before heading home to embark on a similar voyage (including a visit to Shakespeare’s Globe in London) to gain insight into bringing the hallowed spots like Shakespeare’s Birthplace on Henley Street and Hewlands Farm (which now goes by Anne Hathaway’s Cottage; Shakespeare’s wife Anne is renamed Agnes in Hamnet) to the screen and why the obsession with Shakespeare continues in 2025.

Hamnet is a film about immense grief, which Shakespeare—and, according to the movie—his wife worked through as Will staged Hamlet, inspired by the death of his son, at The Globe. As such, Stratford-upon-Avon, even today, is a place where that relationship between art and healing is immensely felt. That’s something that I experienced on my recent trip, and the Hamnet crew worked diligently to harness as they captured the area and that feeling it evokes on film.

Crombie hadn’t been to Stratford-upon-Avon before getting the Hamnet gig, but immediately understood the weight of the task at hand after her first visit: “The other thing that was, and you would know this better than anyone, you realize the cultural importance. There were people from all over the world doing that [Birthplace] tour, and it’s the same with the Globe.” I had a similar experience on my recent tour of the Globe, visitors came from Italy, Saudi Arabia, Ireland, and the U.K.

Stratford-upon-Avon is not a Westworld-style Tudor theme park, but much of the street system shares the same footprint that the Shakespeare family walked. You can follow in their footsteps, across the medieval Clopton Bridge to Shakespeare’s Birthplace. While additions have been made to this 15th-century property and hallowed spots like Hewlands Farm, the bones of each home predate William and Agnes; both have original flooring in one room. (Hewlands Farm now goes by Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.)

There is also an alternate timeline where the actual Birthplace was dismantled, shipped, and rebuilt in the U.S. Entertainer P.T. Barnum was an interested party when the property was put up for auction in the 1840s, underscoring its enduring pop culture prominence.

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust successfully purchased the hallowed spot in 1847. The independent charity has been custodian ever since and welcomes the attention Hamnet brings. “We hope the film inspires more people to come and walk in Anne (or Agnes), William, and Hamnet’s footsteps so they can experience first-hand the love and loss that is at the heart of their story,” says Rachael North, the organization’s chief executive.

The real home, as I saw and hundreds of thousands of visitors each year see, exists, but the Hamnet crew built a version at the U.K.’s legendary Elstree Studios, and filmed there.

“I think there was a conversation about [filming on location] at one point, but these buildings are too precious,” Crombie says. Still, the landmarks provided plenty of inspiration. “We knew what we were looking for, so when it came time to put it in, we were able to do it efficiently in terms of design,” Crombie says. “Then the challenge was, how do you then make that place feel like it’s centuries old, not nine weeks old?”

Hewlands Farm, where Will first encounters Agnes while he tutors her brothers, was, however, shot on location at Cwmmau Farmhouse in Herefordshire. As with the real Hathaway residence, the Grade II-listed building has undergone renovations that are no longer entirely faithful to the 16th century. “Our job was to bring it back [in time],” says Crombie. “We were applying beams into the house, hiding contemporary door frames, and returning it to what it would have been.”

Other sets had the smoke-and-mirrors of giving the impression of age and hefty materials that were actually plywood and plaster. “Even when we created the backyard, the cobbles, they’re not real. But it’s so beautifully done and so beautifully painted,” says Crombie.

Growing up in a prominent tourist destination means taking much of it for granted. I have certainly enjoyed the gardens and other outdoor spaces that Agnes thrives in, and it is noticeable how prominent the greenery is at each location—even on a cold, but sunny November day during my visit.

“The big thing for me with those [Henley Street and farm] gardens was that they needed to be practical, functional. They were not decorative,” says Crombie. Rather than box-fresh, Crombie worked hard with her greens team to source older plants. Whereas the production designer wasn’t afraid to be loose with historical accuracy in some areas as long as it feels good—“It’s not helpful to be rigorous about ‘No, that wouldn’t be there’ or ‘they wouldn’t have had that”—Agnes’ gardens were another story. “They were meticulously researched. It was very important that we be accurate with the plants,” she says.

Accuracy when it came to the film’s recreation of The Globe is a more complicated story.

The first Globe burned down in 1616 mid-performance, giving Crombie some freedom when imagining the arena for the film, as there were no illustrations of the interior at her disposal. (The second Globe lasted from 1614 to 1644.) The Globe reconstruction, which opened in 1997, conveys a sense of intimacy between the audience and the actors. The original theater’s capacity was 3,000 people; the current is 1,600.

Crombie made the Hamnet Globe even smaller to give “this real feeling like you are feeling with the audience when you’re on the stage.” During my tour, Pinocchio was in rehearsal, offering an additional lived-in experience as I watched the technical aspects and performances come together. No ghosts, or Paul Mescal, lingering in the wings—or none that I saw.

Specters of the past come in all forms. Shakespeare’s work stands the test of time because of its universal themes. “I designed Hamlet in Australia at the Opera House, a beautiful, lovely production, but I didn’t engage with it in the way I’ve now engaged with that play,” says Crombie. “I think the way that the film has shown explicitly the importance of art as an avenue for understanding yourself, understanding others, and processing life. We were making it, [and] so many of us were processing things in our lives.”

Crombie goes on to explain that her father was dying during production. “I was talking to him on the phone every day, driving to work, and I remember talking to Chloé about it. At the end, she said, ‘Your father is in every frame of this film.’ He is,” Crombie says. “I was processing my life through the work that I was putting into the film. This crazy parallel, but that’s why it [Hamlet] remains, because we can identify.”

Walking the streets of where I grew up, it was impossible not to think of my own father, who died in 2016. In fact, I was staying at Alveston Manor, the hotel where my parents had their wedding reception more than 50 years earlier. A tree on those grounds purports to be the location of Shakespeare’s first kiss.

Life and death criss-cross in the Bard’s plays and his hometown. The Holy Trinity Church appears in the background in Hamnet, and is another significant landmark; Shakespeare was baptized and buried here. While his wife and oldest daughter, Susanna, lie next to him inside the church, his younger children Judith and Hamnet’s graves are lost to time. In 2022, the Shakespeare twins finally received their own memorials in the Holy Trinity graveyard—a project spearheaded by O’Farrell.

Present and historical cultural touchstones are tangled in the town where William Shakespeare was born and died. In my Uber from Anne Hathaway’s Cottage to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre for a tour, I could hardly believe my ears when Taylor Swift’s “The Fate of Ophelia” began playing on the radio. Coincidence? In 2025, I think not.