No one’s movies move quite like Steven Soderbergh’s, and he continues to hone his unique cinematic rhythms with Black Bag.

A spy thriller that feels like a cross between John le Carré and Agatha Christie, the director’s latest—written, as was his prior Presence, by Oscar-winning screenwriter David Koepp—is at once clipped and fluid, as sharp as a dagger and as silky as luxury bedsheets. Attuned to the cunning and methodical machinations of its protagonists, and exuding a sexy, confident spirit, Black Bag, which hits theaters March 14, is additional proof that, when it comes to sleek, stylish genre movies, Soderbergh remains a maestro at the top of his game.

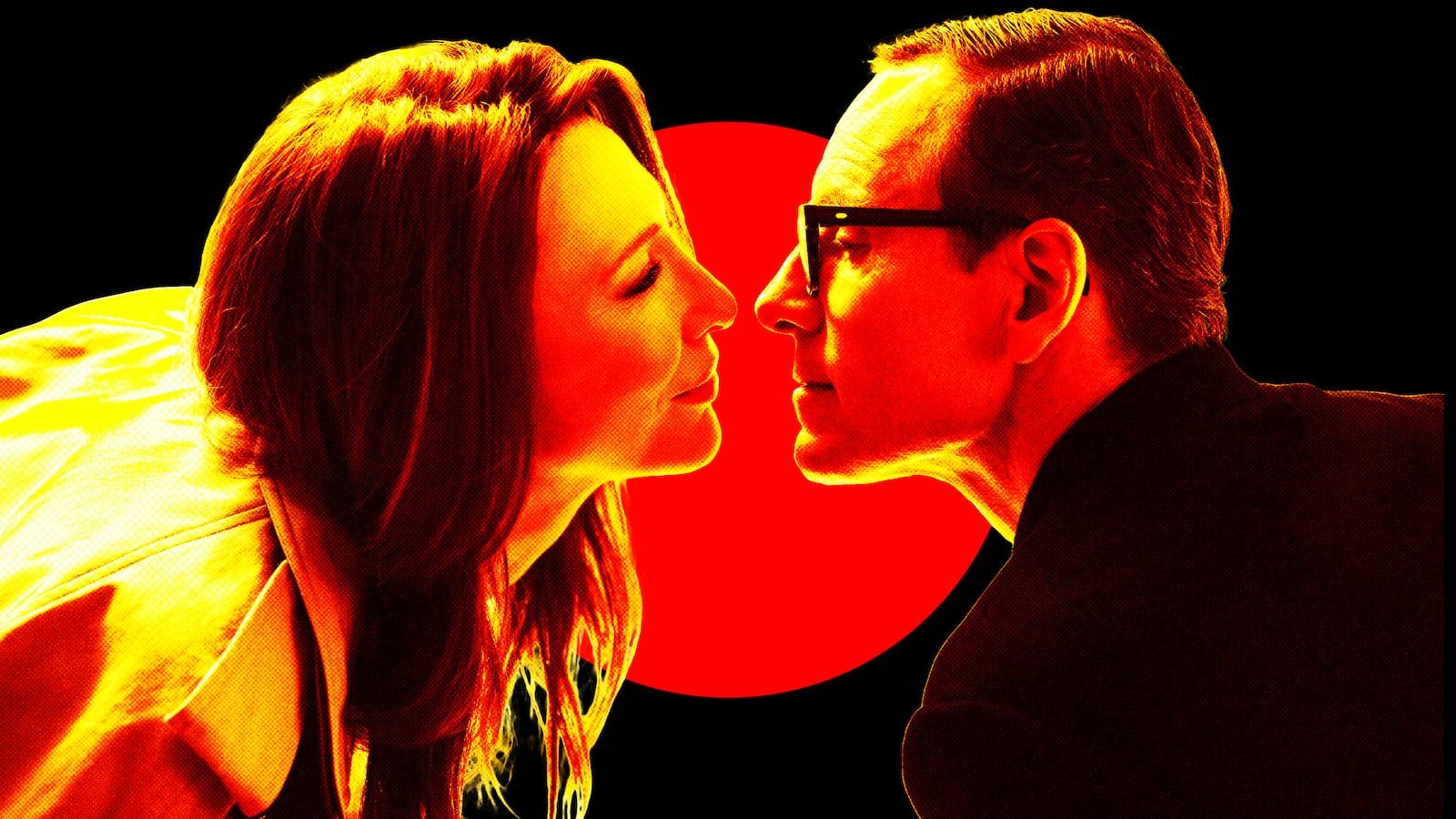

“Fun and games” are the order of the day for George Woodhouse (Michael Fassbender), an intelligence agent who learns from a contact that a very important program known as Severus—which has the power to kill tens of thousands—has been stolen from his agency. Worse, there are five individuals who had the capability, clearance, and motive to commit this crime, and one of them is George’s beloved wife and colleague Kathryn (Cate Blanchett), to whom he’s so loyal that George’s comrade half-derisively chastises him for his “flagrant monogamy.”

Reacting to this news with an expressionless face that speaks to his robotic demeanor (later, someone else will wonder if he’s even human), George is given one week to discover the rat in his midst before all hell breaks loose.

One-upping its iconic spiritual predecessor from Goodfellas, Black Bag opens with an extended single take that follows behind George as he traverses nocturnal London streets, enters a nightclub, makes his way downstairs to a thumping dance floor, locates his acquaintance, and ascends a different staircase to chat outside. In terms of bravura scene-setters, it’s a doozy, and all the more impressive for only delicately calling attention to itself.

The same is true of Soderbergh’s direction as a whole, marked as it is by frequent sequences in which the camera glides alongside characters as they briskly walk through corridors, around corners, and in kitchens and bedrooms. Set to David Holmes’ jazzy score, the film navigates space with velvety purpose, and its suaveness is amplified by use of blooming lights—candles on a pristinely arranged dinner table, fluorescent bulbs over offices furnished in metal and glass—and sumptuous shadows.

Chopping vegetables with the efficiency of a trained cook—and, just as importantly, a man who knows how to wield a blade—George plans to deduce who’s stolen Severus by hosting a dinner party for his suspects. Kathryn approves of this tactic, although she warns her husband to go light on the truth-serum narcotics he’s sprinkling on his guests’ meals.

Staring at his wife before everyone arrives, George is told by Kathryn, “I can feel when you’re watching me,” and it’s a good thing that she likes it, because George is nothing if not keenly aware of everything in his vicinity, including his wife’s maneuvers. When the attendees sit down to eat, it’s no surprise to hear that George is a legendary master of the polygraph, and is also so good at what he does, and so dedicated to the truth (“I don’t like liars”), that he torched his own dad’s career and marriage for being an “inveterate cheater.”

Black Bag is an espionage mystery about marriage and, specifically, the honesty and duplicity that define short- and long-term unions. Koepp’s script playfully wrestles with that idea while twisting his characters up in knots, beginning with the film’s early centerpiece dinner scene, during which George and Kathryn are joined by two fellow agents (Tom Burke and Regé-Jean Page) and their respective girlfriends, a data scraper (Marisa Abela) and a psychologist (Naomie Harris).

George proposes that, for entertainment, they go around the room articulating one “resolution” (like those made at New Year’s) for the person sitting to their right. Knowing George and Kathryn’s reputations, everyone is on guard about this diversion. Nonetheless, they comply, and in short order, sparks fly, culminating with one individual violently affixing another’s hand to the table with a knife.

As George explains to Kathryn, this get-together is the rock designed to cause ripples, and in its aftermath, he begins chasing clues—some of which, including a movie ticket in a trash can, a business trip to Zurich, and strange coordinates, point to his spouse. Such sleuthing leads to complications that put George in professional jeopardy, and Fassbender embodies his spook with a brand of cold, pokerfaced expertise and resolve that, on the heels of his performances in The Killer and The Agency, is fast becoming his trademark.

Blanchett is equally elegant and in control, her every spoken word a study in ambiguity, and she and Fassbender are ideally matched as partners in life and work whose bond is maintained by a careful balance of (and battle between) trust and wariness, independence and devotion.

Black Bag’s title refers to the figurative location where classified information is held, and in this saga, it serves as a convenient excuse for not divulging potentially thorny things. Lies are everywhere as George endeavors to unmask the mole attempting to carry out an attack with enormous geopolitical ramifications, and if that cataclysmic plot is simply a MacGuffin, it serves its purpose as a vehicle for Soderbergh and Koepp’s investigation of the marital ties that bind.

Everything ultimately wends its way back to where it began, with Kathryn rightly proclaiming, “I haven’t had this much fun in years.” The fact that Pierce Brosnan ultimately joins the fray as George’s boss—who has his own reasons for wanting to bring this crisis to a quick close—merely augments the proceedings’ sly panache, which is epitomized by Blanchett reaching across Brosnan in an elevator to select a floor, her gesture a subtle act of triumphant one-upmanship.

Similar to Kimi and No Sudden Move, Black Bag is a Soderbergian genre riff that enhances conventional devices and pleasures with spiky interpersonal dynamics. A film about watching (and analyzing) that proves a transfixing whodunit involving liars and lovers, it’s canny and compact, sultry and sinister. Moreover, it’s precisely the sort of assured and invigorated—and adult—big-budget, star-driven affair that Hollywood has largely forsaken and yet desperately needs.